Julia August Button was born on July 20, 1876 in Auburn, New York to Charles Cooper Button and Clarissa Angeline Rathbun. Charles worked as a teller at the historic Cayuga Co. National Bank. Julia was the second child joining older sister Mary Rathburn. The family continued to expand welcoming Frances Harriet in 1878, Charles Edward in 1880, and Ruth Louise in 1883.

Julia and her sister Mary were baptized together at the Second Presbyterian Church on August 3, 1879.

Tragedy struck the family in early May 1884 when Charles Cooper was stricken with pneumonia and passed away one week later. Guardianship of Julia and her siblings was granted to Charles’s father James D. Button. City directories show that James live two houses down from the family and worked as the physician for the nearby Auburn Prison. James passed away in late 1887 and at that time Clarissa was granted guardianship of her minor children.

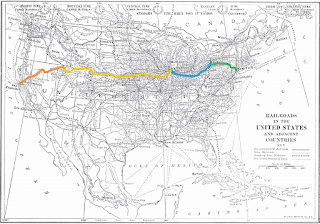

Clarissa remarried on Feb. 27, 1889 to Charles Wesley Smith, a local school teacher. In the early 1890s, the family moved across the country and settled in Seattle where Charles found work first in real estate and then as the librarian for the Seattle Public Library.

Following in her older sister Mary’s footsteps, Julia began classes at the University of Washington on September 4, 1895. Tuition for all students at this time was free to Washington state residents. She attended through the 1896-1897 school year but did not earn a degree.

In 1900, Julia and her younger sister Frances entered the nurse training program at Seattle General Hospital. In early 1902, Frances contracted typhoid fever and meningitis. Sadly, she lost her battle and passed away at the young age of 24 on May 29. Julia graduated from the Seattle General Hospital training on September 30, 1902 and then found work in private nursing.

Julia’s brother Charles Edward left Seattle in 1902 and traveled back to New York to enroll in Cornell University. Unfortunately, during his second year at school the town of Ithaca faced a large typhoid outbreak and he was one the students stricken with the disease. He returned home and then traveled to Arizona to try to regain his health. While in Arizona, his condition worsened and he was stricken with tuberculosis. On February 12, 1907, Julia said goodbye to another sibling when Charles died at the age of 26.

In 1909, Washington state established the Washington State Board of Nurse Examiners which provided examination and educational requirements for all nurses. Julia submitted her application and became a registered nurse in September 1909.

Julia continued to live with her mother and stepfather in a house at 930 26th Ave, seen in the photo the right. By 1910, Charles had left his position at the Seattle Public Library and began a new career as a partner in the law office of Smith & Kelly.

Julia’s work as a private nurse took her to locations around the state. When she renewed her nursing license in 1914, she was taking care of Elizabeth Baker at her home in Walla Walla, Washington.

In the summer of 1918, she answered the call for nurses when the United States entered World War I and was sent to Camp Taylor in Louisville, Kentucky for training. On August 25, 1918, she boarded the steamer France in New York City with fellow nurses on their way overseas to serve their country at Base Hospital 50.

After 8 months overseas, Julia boarded the U.S.S. Santa Rosa in Bordeaux, France to return home. Unlike her voyage over, she was the only nurse on board along with 1,868 service men, 42 officers, and 50 prisoners. She stepped back on American soil early on June 28, 1919. She returned to Seattle and continued working as a private nurse residing with her mother and step-father.

In early 1922, Julia’s mother Clarissa came down with pneumonia and passed away at the age of 74.

She left private nursing by 1924, and found work as a physiotherapy aide at the United States Veteran’s Bureau in Seattle. She remained in this role until shortly before her death.

In the 1930s, Julia resided at the University Women's Club in downtown Seattle. By 1940, she had moved in with her divorced sister Ruth Fowler, and her two grown children, Betty and Harry in a nice home in the Queen Anne neighborhood of Seattle.

In the summer of 1945, Julia was admitted to the United States Marine Hospital in Seattle and was diagnosed with aleukemic myeloid leukemia. Two months later on August 15, 1945, Julia Augusta Button passed away at the age of 69. She was buried next to her mother and siblings.

Sources:

- Ancestry.com. 1880 United States Federal Census[database on-line] Census Place: Auburn, Cayuga, New York; Roll: 813; Family History Film: 1254813; Page: 227C; Enumeration District: 003; Image: 0218

- Ancestry.com. 1900 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Census Place: Seattle Ward 1, King, Washington; Roll: 1744; Page: 8A; Enumeration District:0085; FHL microfilm: 1241744

- Ancestry.com. 1910 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Census Place: Seattle Ward 3, King, Washington; Roll: T624_1659; Page: 3B; Enumeration District: 0092; FHL microfilm: 1375672

- Ancestry.com Source: Year: 1920; Census Place: Seattle, King, Washington; Roll: T625_1929; Page: 11A; Enumeration District: 258; Image: 553

- Ancestry.com. 1930 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Year: 1930; Census Place: Seattle, King, Washington; Roll: 2499; Page: 3A; Enumeration District: 0137; Image: 288.0; FHL microfilm: 2342233

- Ancestry.com. 1940 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Census Place: Seattle, King, Washington; Roll: T627_4377; Page: 62A; Enumeration District: 40-131

- Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

Auburn, New York City Directories 1874, 1876, 1879, 1886, 1888-1891

Seattle, Washington City Directories 1893-1943

- Banta, Theodore M. Sayre Family: Lineage of Thomas Sayre, a Founder of Southampton. New York: The De Vinne Press, 1901. Print. Page 474

- C.E. Button, Who Recently Died in Arizona. The Seattle Daily Times. Saturday, Feb. 16, 1907.

- Eight Nurses Leave to Seattle to Take Up Duties at U.S. Camps. Seattle Times May 25, 1918

- Julia Augusta Button. Department of Licensing, Business and Professions Division, Registered Nurses Licensing Files, 1909-1917, Washington State Archives, Digital Archives, http://digitalarchives.wa.gov

- Manual of the Second Presbyterian Church of Auburn, N.Y. Auburn, N.Y: Knapp & Peck, 1880. Page 46.

- Miss Button Passes Away. The Seattle Star. Friday, May 30, 1902. Page 4. Accessed via Newspapers.com http://www.newspapers.com/image/221358103/

- The National Archives at College Park; College Park, Maryland; Lists of Incoming Passengers, compiled 1917-1938; NAI Number: 6234465; Record Group Title: Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774-1985; Record Group Number: 92; Roll or Box Number: 303

- Rathbone Genealogy, Volume 1 (1898) MyHeritage.com [online database]. Lehi, UT, USA: MyHeritage (USA) Inc. https://www.myheritage.com/research/collection-63424/rathbone-genealogy-volume-1-189

- Department of Licensing, Business and Professions Division. Julia Augusta Button. Registered Nurses Licensing Files, 1909-1917, Washington State Archives, Digital Archives, http://digitalarchives.wa.gov

With the war finally over, and the stream of wounded beginning to slow, the men and women of Base Hospital 50 were finally in a position to relax and enjoy the Thanksgiving holiday which took place on Thursday, November 28, 1918.

With the war finally over, and the stream of wounded beginning to slow, the men and women of Base Hospital 50 were finally in a position to relax and enjoy the Thanksgiving holiday which took place on Thursday, November 28, 1918.