"At Detroit, Mich., one member of the Unit met his best girl and took advantage of the delay caused by replacing a broken truck, to get married at the depot."

1

The journey east by train was recalled as being "very pleasant" by the men of Base Hospital 50 "with a few incidents of special note to be remembered." No doubt the marriage of Private First Class Leigh Thompson and Thelma Wellington was one of those incidents. Thelma and her family planned to meet Leigh's train as it passed through Detroit, but an unexpected delay provided the opportunity for an impromptu wedding. Their marriage was the culmination of a romance begun in Seattle five years before.2

Thelma Grace Wellington was born on January 16, 1895, the second of Albert Lincoln Wellington and his wife Jessie Victoria Eddy's three daughters. Like her sisters, Marguerite and Frances, Thelma was born in Chicago.3 Together with her parents, Thelma moved to New Orleans where the family was enumerated in the 1910 census.4 Shortly thereafter her family moved to Washington, first to the Everett area and then Seattle, where she entered Broadway High School in September of 1911.5 Thelma graduated in 1915 and Broadway's yearbook, the Sealth, described her as "studious and quiet, actions sweet and kind." How Thelma and Leigh met is unknown, but they must have become acquainted shortly after the Wellington family arrived in Seattle.

Leigh Oliver Thompson was the older of two children born to Robert Oliver Thompson, a native of Scotland, and Jane "Jennie" Smaling. Leigh was born in Havelock, Nebraska, on December 28, 1893, and lived in Kewaunee, Illinois, before moving to Seattle about 1910.6 Leigh seems to have left school at an early age as he is working as a clothing salesman at sixteen. At the time Leigh registered for the draft he was employed as a clerk at the Dexter Horton Bank.7

Thelma and Leigh became engaged in August of 1917. At the time of their announcement, Thelma's parents had recently moved to Detroit.8 In April 1918, Thelma traveled from Detroit to Seattle to see Leigh off as he, and the other members of Base Hospital 50, made their way to Camp Fremont for training.9

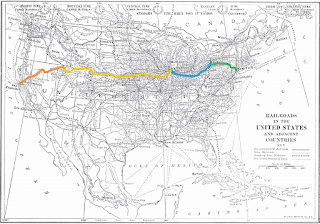

Once Base Hospital 50 was eastbound for New York in early July, Leigh telegraphed his fiancée when he learned the unit would have a 45-minute stopover in Detroit on Tuesday, July 9, 1918. At the appointed time, Thelma and her family arrived at Detroit's landmark

Michigan Central Depot, expecting only to have a short visit with her fiancé. When the departure was delayed, Leigh "used such persuasive powers" as to convince Thelma to marry him at once. "A hurried trip was made by automobile for the marriage license and the clergyman. The wedding took place in the lobby of the station witnessed by the bride's family and all the officers of the unit."

"An atmosphere of much romance" surrounded the couple, when after a delay procuring a license at city hall, the train was held while they were married in the Depot lobby by Rev. W. L. Torrance of the St. Andrew's Episcopal Church, who was hastily summoned to serve as the officiating clergyman. Thelma's father Albert and sister Marguerite served as witnesses. "There was no wedding ring so the bride drew off her grandmother's wedding ring, which she wore on the other hand and it did duty for a second ceremony."10

|

| Detroit Times, July 10, 1918, pg. 2. |

Following the ceremony, Thelma returned home with her parents and remained in Detroit for the duration of the war. After Base Hospital 50 returned from France in May of 1919, the young couple was finally able to begin their married life together. They welcomed a son, Donald Eddy Thompson, in 1926. Leigh returned to work as a bank clerk and later worked as a bookkeeper for the

Continental Baking Company in Seattle.

Leigh died of a heart attack at his home, 3233 Hunter Boulevard, on December 11, 1958 at the age of 64.11 He had been active in organizing Base Hospital 50 reunions, serving as the organizing committee's treasurer, in addition to Commander of the Lake Washington Post 124 of the American Legion and a member of Posts 8 and 40. Thelma also worked in the office of the Continental Bakery from 1945-1959. She died at the at age of 68 on November 11, 1963.12

References:

- United States. Army. Base Hospital No. 50. The History of Base Hospital Fifty: A Portrayal of the Work Done by This Unit While Serving in the United States and with the American Expeditionary Forces in France. Seattle, Wash. : The Committee, 1922. Page 65.

- "Society." Seattle Daily Times, July 17, 1918, pg. 6.

- Illinois, Cook County, Birth Certificates, 1871-1940," database, FamilySearch (familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q239-NVR2 : 6 July 2018), Thelma Grace Wellington, 16 Jan 1895; Chicago, Cook, Illinois, United States, reference/certificate 291650, Cook County Clerk, Cook County Courthouse, Chicago; FHL microfilm.

- "United States Census, 1910," database with images, FamilySearch (familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MPYL-PGG : accessed 7 July 2018), Thelma G Wellington in household of Albert L Wellington, New Orleans Ward 14, Orleans, Louisiana, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) ED 223, sheet 6B, family 106, NARA microfilm publication T624 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1982), roll 524; FHL microfilm 1,374,537.

- Ancestry.com. U.S., School Yearbooks, 1900-1990 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: Thelma G. Wellington, Broadway High School (Seattle, WA), 1915.

- "United States Census, 1910," database with images, FamilySearch (familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MGVD-VFX : accessed 7 July 2018), Lee Oliver Thompson in household of Robert O Thompson, Seattle Ward 3, King, Washington, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) ED 94, sheet 9B, family 197, NARA microfilm publication T624 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1982), roll 1659; FHL microfilm 1,375,672.

- "United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918," database with images, FamilySearch (familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:29JH-4QW : 7 July 2018), Leigh Oliver Thompson, 1917-1918; citing Seattle City no 12, Skagit County, Washington, United States, NARA microfilm publication M1509 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 1,992,013.

- "Society." Seattle Daily Times, August 20, 1917, pg. 11.

- "Society." Seattle Daily Times, April 11, 1918, pg. 6..

- "Persuades Her to Wed Him as Train Halts at Station on Way." Seattle Daily Times, July 21, 1918, pg. 4.

- "Leigh O. Thompson." Seattle Times, December 12, 1958, pg. 45.

- "Mrs. Leigh O. Thompson." Seattle Times, November 13, 1963, pg. 17.

With the war finally over, and the stream of wounded beginning to slow, the men and women of Base Hospital 50 were finally in a position to relax and enjoy the Thanksgiving holiday which took place on Thursday, November 28, 1918.

With the war finally over, and the stream of wounded beginning to slow, the men and women of Base Hospital 50 were finally in a position to relax and enjoy the Thanksgiving holiday which took place on Thursday, November 28, 1918.